Cam LaPorte, "Community Renewable Energy Initiatives: Providing Green, Equitable Energy through Disrupting Power Structures", Energy Research Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, (June 2, 2020).

My investigation into the sociopolitical elements surrounding energy vulnerability kept bringing me to one concern; agency for the consumer. Initially considering landlord-renter relationships as an area for consumer control, I shifted gears towards examining a more broadly-applicable concept - rather than looking into control of external sources of power amidst housing situations, I've been examining direct control of the sources of power of which a community utilizes. In doing this investigation, I came across the concept of Community Renewable Energy - situations of which consumers of energy are also the producers of such energy.

Community Renewable Energy initiatives (also called Renewable Energy Communities, or simply Energy Communities), or CREs, are seperate socio-legal institutions that revolve around a community - varying in scale - taking control of their energy production and consumption, severing their ties to the traditional grid-based utility-provided energy solutions. Different in organizational structure dependent on the community's needs, these solutions allow community members to:

a.) Provide greater energy equity to members within the community, fighting potential vulnerabilities

b.) Seperate their energy usage from the organizations that otherwise control it, putting the power (literally and figuratively) in community members' hands

c.) Give greater bargaining power between these communities and different political entities, utilities or otherwise

d.) Educate community members on tenets of energy justice and energy rights through lived experiences

The video below provides a great overview of the concept of CREs, and the ways in which members or communities feel about the prospect of removing themselves from energy utilities.

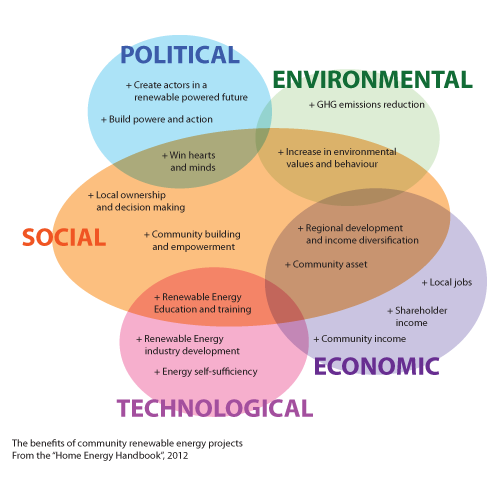

The Benefits of Community Renewable Energy Projects. Reprinted from “Community Renewable Energy – Challenges and Opportunities” by Starfish Initiatives, 2013

a.) In what ways do Community Renewable Energy projects provide greater economic and environmental equity?

b.) What models for community renewable energy initiatives are most effective in disrupting the existing power structures to provide greater equity?

c.) How do we best empower consumers and communities with alternative energy solutions?

d.) What geopolitical situations need to be taken into account when creating CREs?

e.) Are CREs viable for future proliferation and subsequent gaining of global prominence? What barriers exist when considering this forward-looking concept?

As we've discussed ad nauseum in class, the distribution of energy is not always equal; the issues of which cause this inequality are often recursive, overlapping, and contingent upon different sociopolitical factors that consumers largely feel are out of their control. Prohibitive costs, ineffecient or unreliable power supplies, geographical location, household construction, aging infrastructure, and deep-seated political powers all have the potential to negatively effect an individual's experience with energy, causing unnecessary stress, grief, and effort in order to overcome these energy challenges. An energy utility only amplifies these issues; by having the middleperson of a utility, it means that the ability to access energy is not directly available - a third party is necessary in order to power that which needs it in your life. Factor in situations like local policy, housing mandates, landlord requirements, and other such prohibitive elements, it becomes apparent that an individual's connection to energy is tenuously held by the strings of those which allow them to have it. CREs provide the opportunity to subvert these traditionally-held binding factors that perpetuate the cycle of energy inequality and energy vulnerability; they largely cut out intermediary organizations (dependent on the structure of the CRE) and directly put the needs of the community members first. Group, collaborative action gives greater control towards existing energy issues, subverting the need to consult the powers that would otherwise control your energy usage if/when energy problems arise.

The concept of "energy justice" is deeply rooted within the infrastructure of CREs; it seeks to address and connect the different sociopolitical factors (race, class, gender, social justice, climate, income, etc) that impact an individual's energy situation to best address systemic issues regarding energy inequity and energy vulnerability. Due to the immensely variable energy situations that an individual can be faced with (depending on the criteria mentioned above), it's necessary to examine how these different circles interact on an indvidual and social level to best address thos existing problems. Rooted in more widespread "justice" scholarship, the tenets of energy justice considers coexisting elements (like environmental justice) to understand how and in what ways energy issues affect different scopes (micro to macro) alongside the entire energy lifecycle (energy policy, energy production, energy consumption, activism, and energy byproducts [like environmental decay]) to approach these issues moving forward. Of particular interest are the incorporation of these ideals into the "energy transition", from fossil fuel to renewable energy infrastructure - though that's discussed later in the paper.

The above is the Bill of Rights for energy consumers, put forth by the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission. The existence of this document alone reinforces a tenet of energy that is often overlooked - that it's a right to existing in the modern world, and that consumers have rights towards their acquistion and consumption of energy. The verbage is right there in the first blurb; "you have both rights and responsibilities that ensure fair dealings". This document enacts tenets of energy justice, ensuring that the consumer is both a.) knowledgable of their rights and abilities for recourse and b.) there are resources available to help you (such as the PUC) in the situation where there are elements perpetuating energy vulnerability or inequity. This is directly a document intended for usage by a consumer in distress, created by the PUC to better address issues that would otherwise be left unresolved, empowering consumers with information and direction above all else.

Whereas the Bill of Rights provides more prescriptive advice towards resolution of energy justice-based issues, the above article discusses more directly the roots of energy inequity and vulnerabilities, and in what ways they've manifested. It provides value in their in-depth discussion of justice, both in environmental and energy scopes - of which, I posit, are inseperable. Energy justice is inherently tied to environmental justice, as the most equitable energy solutions are those which are, in turn, renewable - the usage of fossil fuels and non-renewable energy sources will always be in favor of those who have the most power already, and are able to decide where those non-renewable sources go. Alternatively, because of the infinitely recursive ability of renewable energy, there doesn't need to be a prioritization because of limited quantity - the actual energy source is better for both the environment and the individuals in the situation, causing less inequities, greener environmental impact, and more of a focus on the infrastructural energy process than the harms/difficulties of the fuel itself. In order to combat energy vulnerability and environmental destruction at the same time, incorporation of tenets of energy justice and equitable energy distribution must be seen throughout the energy transition.

"The Energy Transition" is the terminology given to the present and future movement away from fossil-fuel and non-renewable based energy generation towards cleaner, greener, and sustainable energy worldwide. This shift, being felt differently in varying global situations, is necessary from a climate perspective in order to stop humanity's persistent negative impacts on the environment. Because of this necessary shift from antiquated systems to new, there's room for global improvement on energy systems from a positionality away from just climate issues; if we're to overhaul the existing system to one that's more beneficial to the planet, it's imperative to also overhaul the system into one that's more beneficial to the people. CREs are one such model of doing so - they break away from the existing system of fossil fuels towards renewable energy, while simultaneously increasing energy equity to the communities served. During the energy transition, incorporation of CREs holds massive potential for both the planet and the individuals involved. One such example from the Netherlands is that of the Dutch heat market; they've recently implemented climate policy set to transition energy infrastructure by 2022, which includes legislature for more community-driven facilitation of energy systems. There are benefits exhibited from this recent case-study beyond just climate and equity resolutions, such as increased citizen participation and awareness of energy issues, something which is necessary for inclusion in a CRE. This allows consumers to recognize and combat the existing powers even more than they'd be able to before - existing as a seperate social institution gives bargaining power towards legislative bodies if and when policy change is needed in communities. Regardless of example, moving forward with the energy transition requires those guiding it to examine more issues than just the climate, with CRE technology holding the potential for change amidst this evolving global situation.

One approach towards CRE development is that of the intermediary organization; seen above in Indonesia, and locally with the Community Energy Inc. Rather than having the community directly kick-start an initiative (such as local council members convening, assigning energy experts, seeking out resources, etc), third-party intervention is something of a laissez-faire approach to CRE development. The primary tenet is that the community commissions the third party - Ibeka in Indonesia, and Community Energy in PA - to implement the energy source & resource transmission in the region, of which the community then utilizes. The Indonesian example dives more into detail as to their business model, though that's informed primarily by the different socioeconomic situation between the U.S. and there - though they put a primary focus on continual conversations between different energy-adjacent groups, with the third party acting as a voice for bringing together public and private sectors in the interest of the community. That being said, I think the major pitfall that comes with the usage of a third party is that of accountability & upkeep; there needs to be measures in place to ensure that the community itself is able to be self-sustaining after the critical period of third-party involvement is over. If the intermediary group doesn't provide some variety of training to the community, or impart the tools necessary for upkeep of the energy systems, then they'll always be subject to the whims of the third party in the case that the system goes awry. True energy justice (in this situation) is a result of energy independence, and having the community be self-sustainable beyond the point of a third party's infrastructure development is crucial to ensure this. If a community elects for a third party's usage, there needs to be tenets in place for community education or community empowerment to ensure that they're being treated equitably throughout the energy project's lifetime.

Energy Co-ops are the most recognizable and basely-understandable example of a CRE in the United States; of whose basic concept is that of members becoming "prosumers", or simultaneous producers of the energy that they are consuming. Largely, these organizations involve interested community members coming together and investing in a renewable energy system - like an array of solar panels or windmills - of which pays itself off in energy savings (due to the renewable nature of the system) in the long-run. New members can pay membership dues to contribute to the community fund towards upkeep and expansion of the infrastructure, determined equitably amongst all of the members. Co-ops are largely decentralized from the energy grid, and are exempt from traditionally-bound energy utilities or outside energy actors that would otherwise be putting pressures on the community's energy situation. This isn't always the case, though - the most eminent example in the Philadelphia region, the above Energy Co-op, actually provides green energy to you through the existing grid system AND through the existing supplier (PECO), though I've found this to be a fairly situationally unique solution. Of course, difficulties arise in the general organization of a Co-op; in the situation where all members are to be of equal level, accountability and jurisdictional problems can arise due to the ambiguity of organizational power structures. Distributional concerns, subject matter expert designation, upkeep management, and authoritative decision-making are also locations of conflict - though often times in the creation and kickstarting of a Co-op, there needs to be knowledge acquisition and policy consultation in order to best incorporate feasible solutions into the members' lives. These types of entities are innately disruptive to the existing energy forces - causing more power to fall back into the hands of the consumer, severing their ties to outside forces and redirecting decision-making, energy education, and energy awareness to community members. These tenets are innately incorporated in all varieties of CRE, but in the situation where decision-making and member-input is directly a facet of the situation, these tendencies are experienced even further. Admittedly, energy co-ops are in a fairly infantile stage - only initially attempted and utilized throughout the last decade (and primarily the last 5-or-so years) - but preliminary findings point towards an actualization of the energy justice and energy equity tenets that were discussed in prior sections.

Because of the as-of-yet standardized governance form for CRE creation (rightfully so, as different areas are situated to be best governed by solutions unique to them - though the "CRE-in-a-box" approach is likely to arrive as they gain prominence), social theorists and actualized communities have had the opportunity to experiment with best ways to constitute these non-normative organizations. One such view is the "alternative economy", birthed from a German policy-base that facilitated a freeform market structure and encourages diversely-driven economic development. Therein the analysis is guided by division of labor, capital acquisition, solutions towards internal size and structure, and other guiding sociological principles to cope with the uncertainty of these emerging infrastructures. This alternative economy concept reinforces the bargaining power with which a CRE can have against the existing market forces, providing greater legitimacy and political ability than other counterparts. Incorporating basic economic principles of labor, enterprise, transactions, property and finance into the mix (alongside a potential sixth, geography [to account for their specific situation]) is necessary for the creation of these alternate economies. Membership, identity, and democracy dimensions need to also be put in place to address the issues of those present, alongside having accountability for those involved. Membership-orientation provides an avenue for combatting the exact issues of those involved; of which includes energy vulnerability/inequity, ensuring that energy justice is a part of this model.

Another approach is that of the "socio-legal institution", of which is more focused on the post-energy transition landscape as one that promotes a decentralized and democratized energy source. Energy justice is incorporated in their seeking of "equal footing" as outlined in the EU policy at the top of this column, though gauged in two situationally different locations of the world. The Netherlands' efforts towards energy equity/justice/CRE creation (as shown also above) are primarily controlled by existing or emerging policy by lawmakers, of which will then guide future CRE development in the nation. They also stress the ability for emerging energy structures to tap into and/or sell energy to the grid to provide greater economic spread. Experiences with CREs in the UK, however, have been largely deregulated, and intentionally decentralized - and while the gut reaction would be to point towards the UK as a better example, the situations in which these two nations find themselves causes their approach to be wildly different. The UK is the global epicenter of energy poverty/vulnerability literature - experiences with inequity, lack of justice, and inability to change situations caused this research topic to sprout legitimacy in the first place. This being the case, UK-based endeavors stride for primarily greater equity in their CRE creation to resolve the issues felt there. Conversely, the Netherlands' approach is less directly geared towards combatting energy inequity, and more towards environmental justice (of which energy justice is largely intertwined with) to smooth and empower the energy transition in more effective ways. Thus, the two nations hold two different regulatory and community approaches to CRE development, given their unique experiences with energy and their focus moving into the future. Of course, energy justice and environmental justice are largely symbiotic - but the solutions posited by either nation are more effective towards the solution that works best for them (which, I propose, is the most effective ways to gauge a CRE's organizational structure).

So, where do we go from here? Surely, the topic and implementation of community renewable energy is one of great importance moving into the energy transition, as they hold the potential to combat both existing structural inequalities and promote greener energy that's already necessary moving forward. I'll reintroduce a statement posed earlier; if we're to overhaul the existing system to one that's more beneficial to the planet, it's imperative to also overhaul the system into one that's more beneficial to the people. The primary uncertainty of this type of implementation is that of their structure, discussed to some detail on the left - though given how emergent this type of initiative is, it's safe to assume that there are methods in practice now that have yet to be documented, and methods that have yet to be put in place that could bear more fruit than the already bountiful examples posed throughout this piece.

Clearly, the situationality of the area that is gaining a CRE is instrumental in deciding the way in which that CRE will be designed, run, and operated. Geopolitical situations are guiding forces largely outside of the hands of the consumer which will also impact the ways in which communities bind together to deal with situational difficulties or interpersonal inequities. While grid-based infrastructure varies to some degree globally (as per their energy sources, internal structure, funding methods, governmental control, etc) these have all been paired down by the winds of time - I've failed to provide an analysis on the historical development of global energy grid trends (though a micro-analysis on the different dimensions & inequity in North Carolina was provided), but as with most industries in a capitalism-driven economy, I'm to assume that the models of energy purveyance that failed were consumed by the models that succeeded, albeit regardless of the inequality felt by the consumers of those energy models. The same can be assumed for community renewable energy projects as they gain greater prominence and ubiquity throughout the energy transition. It's a unique position to be in, as we're able to experience the cutting-edge of a global shift and in what ways the global powers will accommodate this shift to better (or worse) suit the needs of their constituents.

Future focus in the area of CREs is that discussed in the Yukon article; of drumming up community engagement, interaction, and excitement towards the prospect of CRE inclusion. While areas where existing community-driven economies are in place are more conducive to CRE generation, how do we best organize communities into excited agents of CRE creation? In what ways have CREs initially been started over time, and what were the specific factors that necessitated these to be created? Of course, the discussion throughout this PECE essay has revolved around either economic or environmental inequities/concerns that spur communities to band together - but are there specific "tipping-point" reasons as to why, and how do we fight the apathy largely felt in combatting these energy systems? How does a single concerned community member make the first step towards initiating this type of model into their area? Similarly, in models that involve initial investment into energy systems, how are we to best address existing fiscal inequality (and potential non-membership due to lack of funds) that are barriers to joining the CRE itself? How are social problems aside from energy-derived ones incorporated into this concept, and how do we ensure equal representation or participation in CREs? While participation in a CRE necessarily involves that individuals be educated in the reasons behind the CRE, and in what ways their own system is beneficial, being able to spread awareness and necessity for these systems is another question in and of itself. The interactive and legislative ability towards CRE functionality only further perpetuates potential community engagement in this emerging infrastructure, but initial discovery and inclusion in one is another necessary area of research.

I've also talked primarily about community (in this definition, town, city, or other interpersonal-groups) being the owners and consumers of energy systems; but other CREs exist which are owned and operated by businesses, of which use the energy they generate and (occasionally) sell the rest to the grid. I would want to look further in depth as to the way that the market structure works to be conducive towards a CRE's goals, and whether or not existing businesses utilizing CREs in a capitalistic society infringes upon the freedom/energy independence that community members would otherwise be facing. More bluntly, does a company's inclusion in a private CRE serve to reinforce the energy inequity and energy exclusivity of which community members are attempting to fight in the first place? While a CRE is innately green for the environment (it's in the name - renewable), and I've largely said that environmental and energy justice are inseparable, I'd be curious to see if there are examples that break this assumption and are negative contributors to community engagement.

Lastly, an examination into the potential cooperation between CREs (and the social/political repercussions that holds) is of great importance. Energy utilities do not live in a bubble, and neither will CREs - will they emerge as a competitive market (like utilities), or will they attempt to maintain the spirit of community equity and work alongside eachother, despite different models? If it's been a particularly cloudy week and a solar-based CRE is having difficulty providing for their members, can a wind-based CRE step in to provide a temporary ballast? This drums up greater questions of the potential inter-grid exclusivity of CREs (more plainly, a grid comprised of different compartmentalized CREs to account for each system's potential downfalls) and in what ways CRE unions could exert political power in their own right.

If the above questions have realized anything, it's that much is in the air for the future of CRE development. They provide an unquestionably valuable path towards combatting energy inequity, vulnerability, and providing energy justice, though the powers guiding their implementation need to be aware of those issues in the first place to ensure they don't get unconsciously reproduced. As we move forward into the energy transition and legislative bodies push for further CRE involvement, it'll become more apparent the ways in which this technology can benefit the latter half of the 21st century - benefitting both the planet that we desperately have to salvage and the community members that are living inequitably. Finding paths forward towards successful implementation of CREs will only encourage their proliferation further, and an awareness of their ability needs to be generated to get community members excited/aware of this possibility. Their power to unite a community under a common issue holds the potential for greater community investment and community political ability than seen before, given the keystone nature of energy in our modern lives. In an effort to combat energy vulnerability, CREs are a valuable method for deciding the future of the global energy landscape and the ways in which energy will interact with our lives moving forward - and I can only hope that they get the recognition deserved of such a potentially system-breaking and world-changing idea.