Roya Haider, "Home is where the heat is: Energy vulneability and forced mobility", Housing Energy Research Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, (June 2, 2020).

Between 2000 and 2010, energy costs in the US increased at 3 times the rate of rent, during the same period, rents rose by 12% and household incomes fell by 7%. These figures should give one great pause as they indicate nothing short of an American crisis in housing stability. To add insult to injury, low to middle income households and people of color bear a disproportionate rate of the cost and energy burden. Based on 2015 data from the Residential Energy Consumption Survey, low-income households use less energy than any other income group. However, they have the highest energy burdens, particularly households with incomes less than $20,000, whose energy burdens are more than twice as high as households who earn $20,000-$40,000

Burden has become the keyword in US energy research and policy, to characterize the portion of a household’s income that is dedicated to rent and utilities. Generally speaking, a cost burden exists when a renter must pay more than 30% of income to rent and an energy burden exists when anywhere between 6%-11% (depending who you ask) of income goes to household energy costs. Elsewhere, terms such as energy “poverty”, “insecurity”, or “ vulnerability” are used to describe states of being, becoming, or even risk for being at a lack of household energy needed to maintain the quality of daily living.

Call it what you will, predicament or process, the vulnerability or insecurity created by energy burden can quickly drive a household into crisis. Though crisis itself may come and go, its effects can be long lasting and pernicious. The effects of high energy burdens on a household’s physical and mental health have been well documented. For example, the issue of mental stress swirls around fears of not being able to pay bills, and asthma and respiratory problems can result from thermal discomfort. But the economic and dwelling consequences may be less understood. This essay seeks to understand the relationship between high energy burdens and the displacement of people from their homes, (sometimes referred to as forced mobility or involuntary displacement) and the subsequent poverty that ensues.

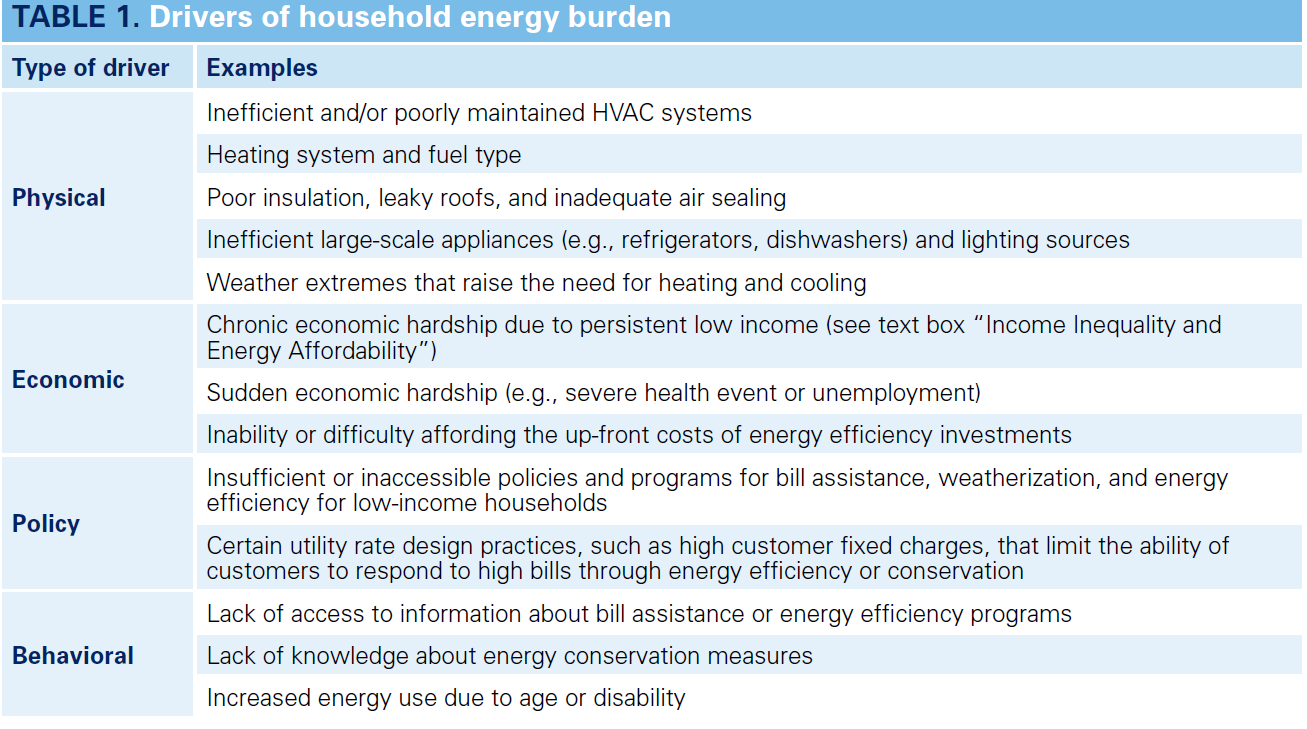

Research shows a number of factors drive a household’s experience with energy burden with physical quality of housing stock and appliances and economic hardships being chief among them.

“Adverse economic and financial consequences often occur when low income households with high utility bills have to make tradeoffs between meeting alternative critical household expenditures.” (Brown et. al., 2020)

For example:

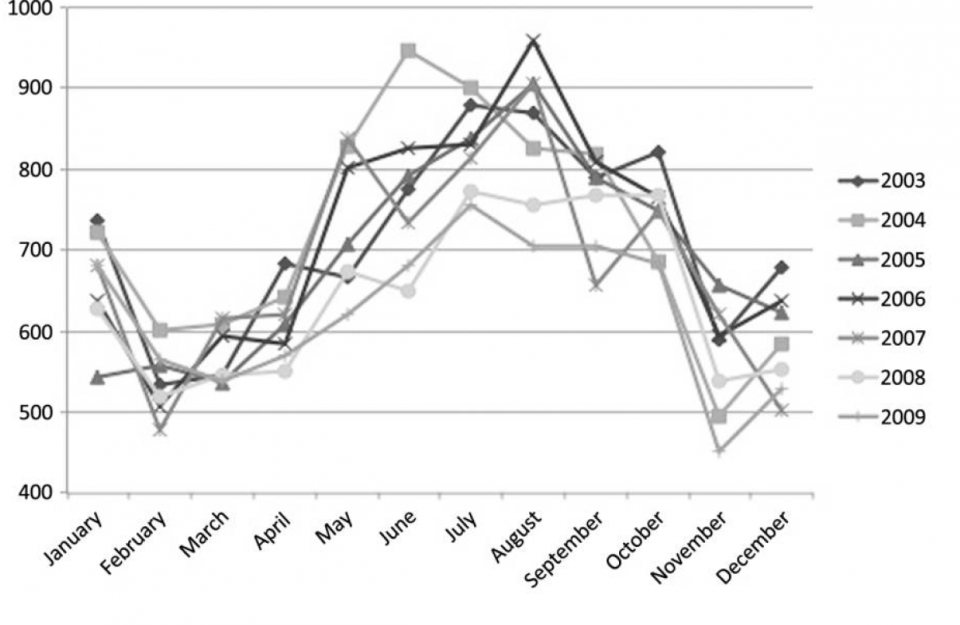

Eviction trends peak tend to peak in the summer months and then fall drastically in the winter.

One explanation for this phenomenon has to do with moratoriums on disconnection enacted by energy providers. When moratoriums begin in November, many households are able to stay current on rent by forgoing their heating bill. In the summer months, they play catch up with the utility company by shorting the landlord and causing a surge of eviction filings in the summer. (Desmond, 2016).

by far the most evictions are results of renters’ failure to pay their rent and utilities. A recent survey by the Eviction Lab suggests that most poor renting families spend over half of their income on housing-related costs, with one out of four spending more than 70% of their income on rent and utilities alone. While the monthly rent is communicated upfront, utility spending is usually not, and may become a major determining factor on whether a family can afford housing-related costs. (Li, 2019)

Housing instability is described as shut-offs resulting from non-payment or frequent residential mobility stemming from an inability to secure proper housing due to high utility expenses and/or a history of utility debt. It is noted as a third consequence of energy burden after illness/stress and financial challenges(Hernandez and Bird, 2016).

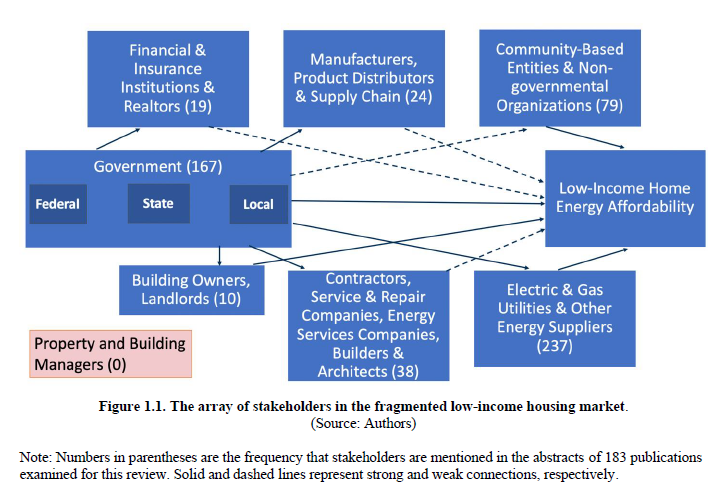

As seen above, solving complex problems such has housing instability, poverty, and energy burden require innovative strategies that cross disciplines and industries. Taking measures to identify and include the proper stakeholders is one place to begin. Take a look at the stakeholder diagram below, which resulted from a literature review done for the Dept. of Energy. Notice the gap identified between landlords and property managers but also notice there is no mention of consumers or residents.

In his book Evicted, Matthew Desmond recognized landlords as "major players in the urban housing market", in an interview he states "Landlords literally own poor communities. They decide who gets to live where. They choose which families to evict and which to spare. They set rents, buy property, and make or neglect repairs. I realized early on that, if I really wanted to understand the dynamics of eviction and the link between housing and poverty, it was essential to capture landlords’ perspectives."

Bridging the gap between the split incentives problem (when landlord incentives and tenant benefits don't match) is another start to healing this problem. Desmond also calls for housing to be brought back to the center of the poverty debate.