James Adams, Alison Kenner, Briana Leone, Andrew Rosenthal and Morgan Sarao. 3 May 2021, "April 2021 Media Brief", The Energy Rights Project, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 29 May 2022, accessed 29 May 2022. https://energyrights.info/content/april-2021-media-brief

One legacy of the pandemic will surely involve a shift in the way we think about, use, and perhaps even pay for energy services. One of the most striking changes has been the sharp increase in demand for high-speed internet access. Indeed, the drive to stay connected and entertained during lockdown resulted in significant gains for Comcast, whose first quarter profits were up by 55%; the vast majority of the increase coming from new or upgraded broadband and phone line services (Rizzo 2021). There seems to be an emergent structure of feeling in which internet access is understood as an essential infrastructure, being deemed integral to social inclusion and success. Thus, rural areas that have traditionally been marginalized in terms of broadband access--such as rural Pennsylvania--have started to become more vocal about their grievances and dissatisfactions (Mamula 2021).

On top of the project expanding access, COVID-19 lockdowns have also altered the way we are thinking about and providing assistance to those who have trouble affording access to energy services. For instance, evidence of a greater appreciation for energy rights can be found in the expansion of rental assistance in Philadelphia to include funds for those struggling to pay their utility bills as well (Bond 2021). We can also see a shift in ideation about the role that energy access plays in the right to a public education. For instance, during the pandemic, Philadelphia’s PHILconnectED program has offered high speed internet to limited income families with children engaged in distance education. More recently, the program has even extended this assistance to families with Pre-K Students (NBC 10 Philadelphia 2021). This effort to provide access to essential infrastructures is no doubt important and commendable, but perhaps the most curious realization to come from this effort is the lack of trust from Philadelphia’s LMI communities and communities of color. According to Philadelphia’s Chief Education Officer, Otis Hackney, these families doubt that they will actually be able to access the internet free of charge. Others are simply hesitant to divulge their personal information to this unknown entity. While, to some, this might register as an irrational fear or evidence of assistance illiteracy, scholars and policy makers should rather recognize it as an informed distrust and an implicit critique.

The experience of Black life in the US, characterised by centuries of racial capitalism (Robinson 2000) and violent exclusions and violations of the social contract (Mills 1997), will not be so easily overcome. As Randall argues in her analysis of Black distrust of the American healthcare system (2006), trust must begin with an explicit recognition of this history of violence and exclusion and the development of a capacity to bring communities of color into the process of generating their own creative solutions to the problems posed by racial capitalist legacies.

This April edition of the Energy Right’s Project Media Brief follows up on the latest news and scholarship concerning the state of energy infrastructures and access to energy services during the pandemic. The discussion of our artifacts for this month is framed by the literature on racial capitalism. Thus, we continue to expose how the pandemic has intersected with other catastrophes and structural inequities in ways that have intensified the forces of structural racism. We also discuss implications of this intersection for performing a just transition to renewable energy and for considering the role that energy services play in the fulfilment of human rights.

A woman holds a Just Transition Now sign at a rally in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Photo by Flickr User Lorie Shaull.

A woman holds a Just Transition Now sign at a rally in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Photo by Flickr User Lorie Shaull.Efforts to transition to renewable energy continue to gain traction across the country. A recent letter signed by thirteen utility companies urged Biden to adopt renewable standards that would "ensure the electricity industry cuts carbon emissions 80% below 2005 levels by 2030" (Reuters 2021). Though the letter did not mention Biden’s goal to decarbonize the entire US power sector by 2035, the authors suggest that their goal is in alignment with this plan. They cite Sam Rickett’s advice (co-founder of Evergreen Action), claiming that focusing on early gains in emissions reduction will be most important, as the elimination of the last lingering fixtures of the fossil fuel economy will be the hardest to achieve. More locally, two new bills were introduced in Pennsylvania (one to the House and one to the Senate) that intend to rescue the state’s fledgling solar industry from the pandemic-induced recession (Butler 2021). The bills would increase the state’s renewable energy goal from 8% to 18% by 2026, which, experts say, could create a significant increase in renewable energy industry jobs and economic growth by 2030.

One of the challenges of this renewable energy transition will be simply finding the space for new, land-intensive renewable infrastructures (Merril 2021). Traditionally, wind and solar arrays have required much more land than gas or coal plants. That being said, Biden’s plan allows for the continued use of nuclear and hydro, which take up less space, and spatial fixes are also being explored and developed for wind and solar (i.e. rooftop solar and sea-based wind farms). Bill McKibben has also noted that the land problem may be offset as the efficiency of renewable technologies keeps increasing. In fact, according to his data, we are already able to produce 100x the global energy demand with solar alone, and using less land than we currently devote to fossil fuel infrastructure (McKibben 2021). The problem this leaves out, however, is where and how this energy can be stored during the interlude between the time of production and time of use. Nevertheless, what remains clear is that a renewable powered global society will need to be spatialized differently, and we have yet to figure this out.

Another important challenge of this transition to renewables, if it is to be a just transition, will be ensuring that people of color and/or low or limited income communities are not left out, or worse, left shouldering the bulk of both the transition’s economic and environmental cost. As many scholars note, the bulk of the human costs of fossil fuel industries, which any just transitions must seek to offset, have been borne by BIPOC communities; the same communities that are now most vulnerable to climate disasters (Gonzalez 2020). Though recent improvements in renewable technologies have rendered renewable energy remarkably cheap (McKibben 2021), the upfront costs are such that it is still out of reach for most low to limited income households. Cities like Philadelphia, with vast income inequalities correlated with racial differences (Shields 2021), have to be extra careful in this regard. As Mingle argues (2021), the fact that more affluent residents are transitioning to renewables ahead of the curve means that those unable to afford the up-front costs of this transition may be forced to finance the maintenance of our aging fossil-fuel infrastructure. Furthermore, the continued use of this dilapidated infrastructure presents risks for both climate and infrastructural disasters, as methane leaks both increase the percentage of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere and also increase the risk of explosions like the one that leveled five rowhouses in Philadelphia in December 2019.

Butler, Michael. “Pennsylvania lost a quarter of its clean energy jobs in 2020. Here’s a proposal to bring them back.” Technical.ly, April 15, 2021.

McKibben, B. (2021, Apr 28). "Renewable Energy Is Suddenly Startlingly Cheap." The New Yorker.

Merril, D. (2021, April 29). "The U.S. Will Need a Lot of Land for a Zero-Carbon Economy." Bloomberg Green.

Mingle, Johnathan. 2021. "Cities confront climate challenge: How to move from gas to electricity?" Pbs.org.

“Power companies urge Biden to implement policies to cut emissions 80% by 2030.” Reuters, April 19, 2021.

As previously stated, a primary challenge of the renewable energy transition will be ensuring that the transition process does not intensify current economic and environmental inequities. Racial and economic gaps in solar adoption, although shrinking, are still significant (Gearino 2021), with the majority of adoptee’s being white and firmly middle class. One strategy for accelerating the process of making solar more economically available to more people is to adopt new models, such as the energy co-op model. In Pennsylvania (and 29 other states in the US), however, archaic laws still prohibit ownership of solar arrays by more than one entity, thereby preempting any co-op model from taking hold (Baker 2021). Though there is bipartisan support for changing this law, these efforts have faced a strong and diverse opposition ranging from those who find solar arrays unsightly to environmental advocates worried about their ecological impacts. But the most militant opposers, by far, have been the for-profit utility companies who believe the co-op model threatens to undermine their profits.

As painfully demonstrated by historians of the racial capitalocene (Vergès 2017), the production of surplus value that underwrites capitalist profits has always been rooted in the creation of social difference through the devaluation of the bodies of people of color (Pulido 2017). And though these structural violences can and do rear their head in everyday life, the extent of the human risks imposed on Black and Brown bodies in the name of capital become all the more apparent during a disaster. The recent Texas power crisis is a prime example.

Though Texas regulators recognized the vulnerability of the Texas grid to extreme winters all the way back in 2011, the responsibility to weatherize and decouple critical interdependencies was largely left to the energy corporations themselves. Given the rarity of these winter events, the profit incentive proved insufficient to motivate these necessary changes. Thus, in 2021, substantial power shortages resulted from freezing infrastructure, causing one of the costliest disasters in Texas history. More than 200 people died during this event from hyperthermia, carbon monoxide poisoning, or the failure of electric medical devices.

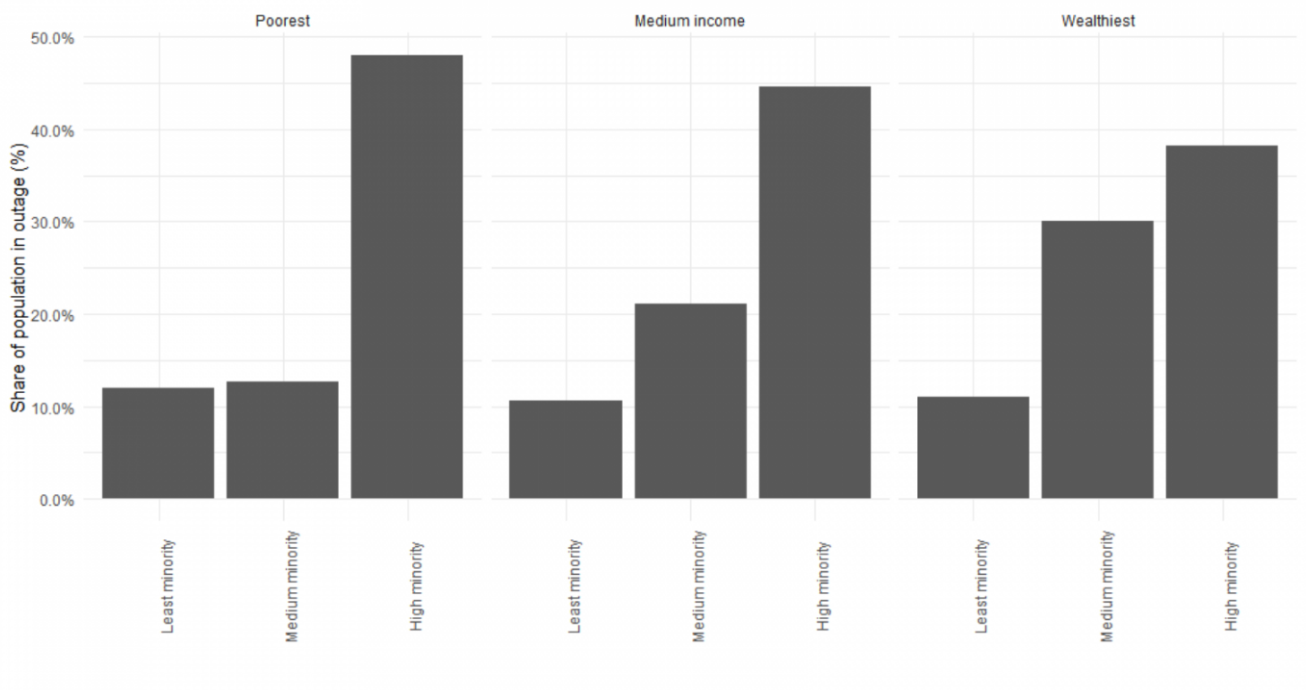

What is more, the economic and human losses were not equally distributed. Controlling for both income level and the presence/absence of critical infrastructure, one study found that communities of color were four times more likely to experience a sustained outage during the storm than predominantly white communities (Carvallo et al. 2021). Another study showed that gaps in regulations requiring carbon monoxide detectors, on top of a general lack of public education about the topic, resulted in the largest CO poisoning event in Texas history. As Trevizo et al. point out (2021), the rates of these poisonings were disproportionately located in communities of color, as those marginalized in terms of legal protection are often equally marginalized in terms of access to information. Thus, a severely disproportionate number of BIPOC Texas residents unwittingly poisoned themselves in their struggle to keep warm in their own homes.

Trevizo, Perla, Ren Larson, Lexi Churchill, Mike Hixenbaugh, and Suzy Khimm. 2021. “Texas Enabled the Worst Carbon Monoxide Poisoning Catastrophe in Recent U.S. History.” Texas Tribune, April 29, 2021.

Carvallo, JP, Feng Chi Hsu, Zeal Shah, and Jay Taneja. 2021. “Frozen Out in Texas: Blackouts and Inequity - The Rockefeller Foundation.” Field Note. The Rockefeller Foundation.

Baker, Brianna. 2021. "In Pennsylvania, a bipartisan coalition is pushing to free community solar from bureaucratic red tape." Fix Solution Lab.

Gearino, Dan. “Inside Clean Energy: The Rooftop Solar Income Gap Is (Slowly) Shrinking.” Inside Climate News, April 15, 2021.

Gonzalez, Carmen. 2020. “Racial Capitalism, Climate Justice, and Climate Displacement.” Oñati Socio-Legal Series 11 (1): 108–47. https://doi.org/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1137.

Johnson, Gaye Theresa, and Alex Lubin, eds. 2017. Futures of Black Radicalism. London ; New York: Verso.

Mills, Charles W. 2011. The Racial Contract. Nachdr. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press.

Pulido, Laura. 2017. “Geographies of Race and Ethnicity II: Environmental Racism, Racial Capitalism and State-Sanctioned Violence.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (4): 524–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516646495.

Pulido, Laura, and Juan De Lara. 2018. “Reimagining ‘Justice’ in Environmental Justice: Radical Ecologies, Decolonial Thought, and the Black Radical Tradition.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 1 (1–2): 76–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618770363.

Randall, Vernellia R. 2006. Dying While Black. Dayton, OH: Seven Principles Press.

Robinson, Cedric J. 2000. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press.

Shields, Mike. 2021. “Philadelphia’s Persistent Income Inequality: A 2019 Data Update.” Regional Direction. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Economy League of Greater Philadelphia. https://economyleague.org/providing-insight/leadingindicators/2021/02/24/phlincomeinequality2021.