Ali Kenner, James Adams, Briana Leone, Morgan Sarao, and Andrew Rosenthal. "Research Brief - July 17, 2020." Energy in COVID-19. The Energy Vulnerability Project. Platform for Experimental and Collaborative Ethnography.

Two of our articles focus on how heat waves intersect with racial and economic inequities, a subject that has received much attention in recent weeks in the wake of increased public attention on structural racism, coupled with mid-summer temperatures in the U.S. Scientists have forecast that 2020 will likely be the hottest year on record, which is particularly worrisome given that so many people rely on public spaces to access air conditioning. Malls, libraries, movie theaters, and community centers are, if not closed, risky places for the elderly and people with chronic disease conditions. In other words: those who most need AC are least likely to have access at home. The disparities in access to cooling infrastructure far precedes COVID-19, as both articles demonstrate.

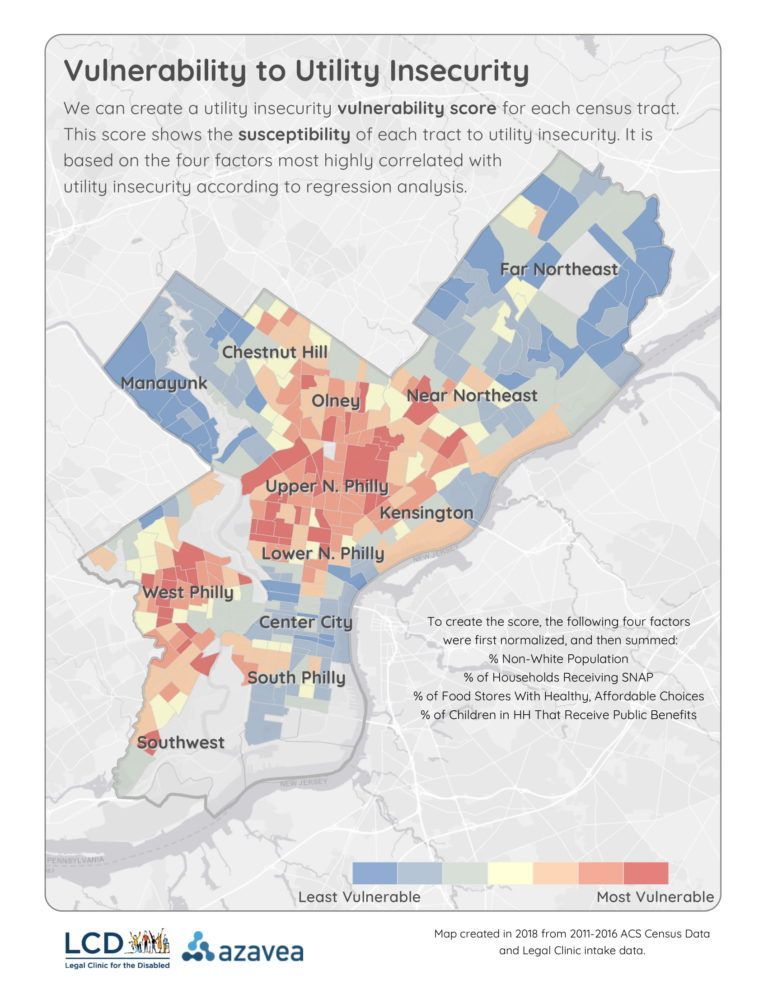

Racism has been built into the very infrastructure of cities, through redlining and urban development, which has left historically Black neighborhoods with less natural cooling, for example. Fewer trees, parks, and other forms of greenspace not only make neighborhoods hotter, but this also makes it more expensive to cool homes. Researchers found that in Philadelphia, disparities between neighborhoods with and without greenspace produced a 22 degree heat index difference. This means that households living in neighborhoods lacking green infrastructure -- such as trees, parks, and community gardens -- will pay more to keep their homes comfortable during summer months.

Another issue is the absence of generational wealth in Black and Latinx households; savings and loans are often needed for homeowners to make basic systems repairs on aged housing stock, yet black and brown families are less likely to have such resources. This is a well-known problem in the city of Philadelphia, where one of the articles focuses its attention. While the federal Weatherization Assistance Program is designed to make low-income homes energy efficient, so that summertime cooling is more affordable, if homes need basic repairs they are disqualified from the program.

Infrastructural issues related to aged housing stock and disparities in neighborhood-level heat index are legacies of structural racism that, during the pandemic, become more risky and burdensome with a lack of access to public spaces for cooling. This is what researchers at the Center for American Progress refer to as “compounding systems of systemic racial and economic inequities within the United States.”

The following artifacts speak specifically to the theme of heat waves, health, and climate change.

Glout & Kelly. (2020, June 29). Extreme Heat During the COVID-19 Pandemic Amplifies Racial and Economic Inequities. Center for American Progress.

Zerbo, R., Rosan, C.D. "Philly's Hot Weather Health Crisis." The Philadelphia Citizen. June 24, 2020.

Our inaugural research brief reflects several themes at the forefront of the current US political climate: statements on how systemic racism impacts energy access and affordability; concerns over how racial and economic inequities make some communities more vulnerable to heat waves; and how digital divides in broadband internet access prevent many households from accessing education and healthcare during the pandemic.

Almost all the artifacts gathered for our inaugural research brief discussed the relationship between energy and structural inequities. Many of the articles highlighted racial disparities specifically, underscoring that Black Americans face more disadvantage from energy infrastructures, including policy. BIPOC experienced greater energy vulnerability, health impacts from fossil fuel emissions and extraction, and had less access to broadband internet prior to COVID-19. In many ways the pandemic exacerbates these inequities.

Diana Hernández, an assistant professor at Columbia University, points out in a webinar, ‘Race and Energy’ that African Americans experience more utility shut-offs than any other racial and ethnic group (the above image was presented by Dr. Hernández during the presentation). In most cases, however, utility companies don’t see these disparities because they collect no demographic information from their customers. As Dr. Hernández puts it, unlike most other sectors, utility companies are mostly flying in the dark when it comes to data. The pandemic may be forcing a change in practice, due to what one Chicago-based community organizer identified as increased visibility on the issue of energy poverty. In Illinois, the new Utility Relief Agreement with utility companies requires companies to provide monthly reports “credit and collections data by zip code.” Karen Lusson, a staff attorney with the National Consumer Law Center noted that this is “important because this information will give the commission and stakeholders the opportunity to analyze what’s happening in particular communities,“and particular with communities of color and whether they’re being disproportionately impacted.” Similar to the foundation of federal and state energy policy, which is narrowly financial in its criteria and assistance, data about the problem of energy vulnerability is known through its economic dimensions often to the exclusion of demographic and geographic information. Like the absence of data on race and ethnicity, little is known about the gender dimensions of energy vulnerability in the U.S.

Kowalski, K. A. (2020, July 2). "Clean energy programs can help address some racial disparities, advocates say". Energy News Network.

Lydersen, K. (2020, July 2). "Utility efficiency programs offer model to merge climate, racial justice solutions". Energy News Network.

“Pecan Street Race and Energy Webinar June 30, 2020.” Pecan Street Inc. Youtube. Last Accessed July 16, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mAFcdBpVW8g&feature=youtu.be

Ruppenthal, A. "What states can learn from Illinois' new COVID-19 utilities relief agreement." Energy News. June 23, 2020.

Andrew Rosenthal’s artifacts highlight responses by Internet Service Providers to what is being termed “COVID-19 usage”, which describes the changing dimensions of energy service use during the pandemic. In a July 1st press release, Comcast frames its latest unlimited data plans within the context of “COVID-level” usage. In addition to making unlimited data more affordable, the company is also zeroing out pre-COVID balances, and keeping their public hotspot network open through the end of 2020. At a glance this appears to be a generous gesture on the part of the tech giant. From another angle it seems to be Comcast’s latest response to earlier criticism that the company’s COVID-19 policies created barriers for low-income households and contradicted long-standing claims about the capacity of its infamous hotspot network. The press release subtly nods to such criticisms in its claim that, “Our data plans are based on a principle of fairness,” which forces the greatest data users to foot the bill for infrastructure development, capacity that Comcast claims doubles every 18-24 months. It is Comcast’s “super user customers” who bear the burden of network development, and always have been. But the company’s privileging of “super user customers” reinforces criticism that not enough is being done to provide access to low-income households, who have met sizable barriers to gaining affordable service since the pandemic began. But perhaps COVID-19 needs will help convince lawmakers and the broader public that internet access is an essential service rather than a luxury regulated by market forces.

A second article on internet access during COVID-19 points to the growing demand (and need for) telemedicine during the pandemic, particularly among vulnerable patients such as the elderly and people with chronic disease conditions. A 2019 article in the Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics underscored internet access as a “super determinant of health”. While many people -- particularly in Philadelphia, where the author lives and works -- have argued that broadband internet needs to be made available in order for schools to operate remotely during the pandemic, less attention has been given to parallel disparities in healthcare access.

Butz, Greg. “Introducing Our New Data Plans: More Data. Lower Prices.” Comcast Corporation, 1 July 2020, corporate.comcast.com/stories/introducing-our-new-data-plans-more-data-lower-prices-better-packages.

Carmen Guerra, J. M. (2020, July 07). Why Internet access is a 'super' determinant of health: Expert Opinion.